- Our nation’s debt is massive and growing at an unsustainable rate.

- Congress has failed to address the looming problem, preferring to kick the can down the road, but that may be changing.

- While stabilizing our nation’s debt will be challenging, it will not be impossible.

- Yet failure to curb borrowing may put upward pressure on long-term interest rates, exacerbating the problem.

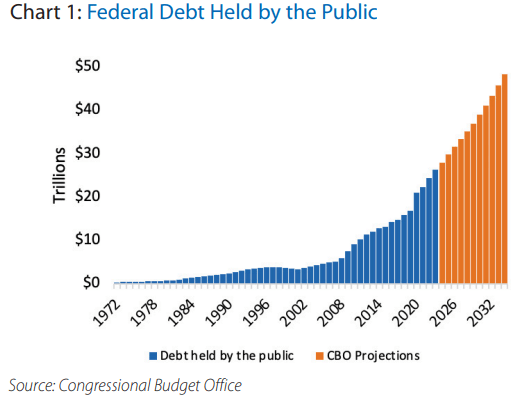

In 2007 our national debt surpassed $5 trillion for the first time. Then the Great Financial Crisis set in, and our debt accumulation embarked on what appears to be an unsustainable path. In the next 10 years through 2017, we tacked on an additional $10 trillion of debt. Since then, in just 6 years, we’ve added $11 trillion more debt.

At fiscal yearend 2023, the Federal debt held by the public was $26 trillion and it is still growing. According to recent projections published by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), the Federal debt burden is expected to increase by $22 trillion in the next 10 years (Chart 1). And we believe this forecast may be understating the growth over that time. We question whether this trajectory can be sustained without consequences.

The primary reason for our growing debt is recurring and pernicious budget deficits. Simply put, debt increases when Federal government spending exceeds revenue. The capacity to carry debt over time enables the government to pay for programs and services important to the public, even when it does not have funds immediately available to pay for that spending. And targeted government spending can facilitate economic growth and support the economy in difficult times. While the ability of the government to run an unbalanced budget is generally understood as a good thing, persistent deficits can lead to trouble and must be managed.

The primary reason for our growing debt is recurring and pernicious budget deficits. Simply put, debt increases when Federal government spending exceeds revenue. The capacity to carry debt over time enables the government to pay for programs and services important to the public, even when it does not have funds immediately available to pay for that spending. And targeted government spending can facilitate economic growth and support the economy in difficult times. While the ability of the government to run an unbalanced budget is generally understood as a good thing, persistent deficits can lead to trouble and must be managed.

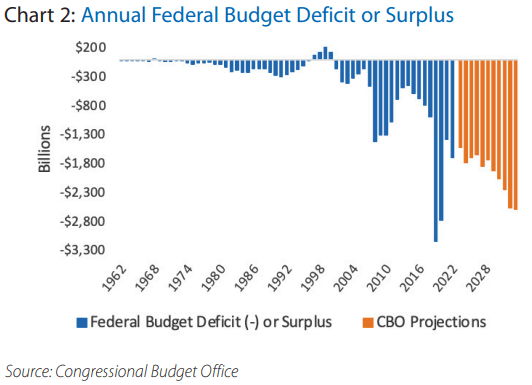

To wit the Federal government has run a budget deficit in each of the last 22 fiscal years (FY). The last time the Federal budget was in surplus was 2001 (Chart 2). This period includes both the Great Recession and the Global Pandemic when the Federal government would have been expected and encouraged to engage in deficit spending to support the economy. It is during better times that fiscal discipline is required to ensure the ability to borrow when it is most needed.

But alas that fiscal discipline is absent now. The economy as measured by real GDP grew by 3.1% last year and the unemployment rate remained below 4%, a level consistent with full employment. Perhaps not a typical period requiring massive fiscal stimulus, yet the Federal deficit rose to $1.7 trillion last year. And according to the Peter G Peterson Foundation, adding back the accounting effects of the student debt forgiveness plan, the FY23 deficit was more than $2 Trillion, despite a healthy economy.

But alas that fiscal discipline is absent now. The economy as measured by real GDP grew by 3.1% last year and the unemployment rate remained below 4%, a level consistent with full employment. Perhaps not a typical period requiring massive fiscal stimulus, yet the Federal deficit rose to $1.7 trillion last year. And according to the Peter G Peterson Foundation, adding back the accounting effects of the student debt forgiveness plan, the FY23 deficit was more than $2 Trillion, despite a healthy economy.

To put that in context if you discount the leap in government deficit spending during the Pandemic, last year’s deficit would otherwise have been the largest on record. The most recent 10-year CBO Budget and Economic Outlook projects sustained annual FY deficits through 2034. Can this be sustained? When looking at these numbers in the context of our economy, we don’t think so.

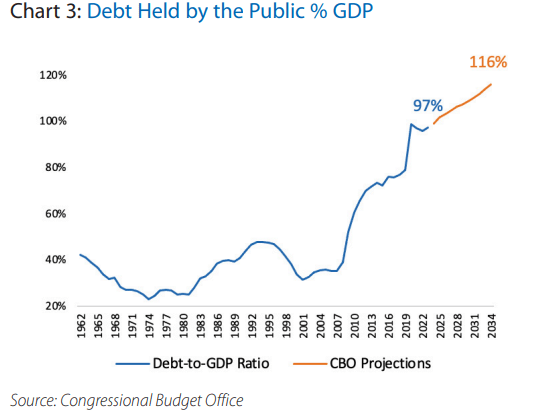

According to the CBO, it is expected that the debt-to-GDP ratio, currently at 97% (again using debt held by the public), is expected to rise to 116% by 2034 (Chart 3) and 172% by 2054. Note that the CBO forecast is based on current law and assumptions about growth, inflation, and interest rates. That means they can change significantly for the better or the worse as conditions change.

Beyond the important dynamic of potentially not having the capacity to borrow when needed to combat issues, like economic downdrafts and financial crises, there are several other repercussions of prolific deficit spending worth considering.

Front of mind is the growing challenge of servicing the debt. In addition to issuing new debt to finance current deficit spending, the Treasury must also manage the existing debt. This requires refinancing, or rolling over, maturing bills, notes, and bonds. In January, the Treasury announced borrowing estimates for the first two quarters of 2024 of $962 billion on the back of $776 billion in borrowing in the fourth quarter of 2023.

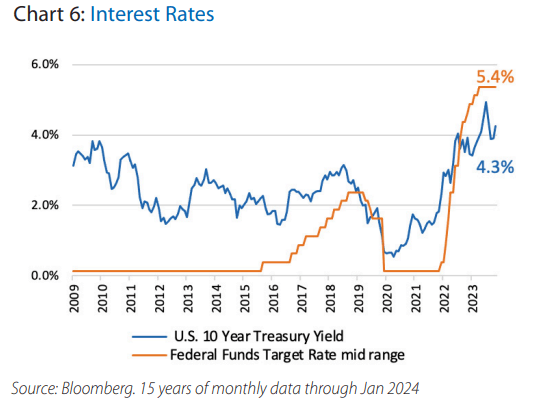

Furthermore, the interest cost on the debt is rising. As of the end of January 2024 the average interest rate paid by the Treasury on marketable debt had doubled to 3.21% up from 1.61% in 2021. This rate will rise further to reflect the Federal Reserve (Fed) target policy interest rate of 5.50%. The lowest yield across the Treasury maturity curve is 100 basis points above the 3.2% average interest rate paid.

According to the St. Louis Fed, 12% of debt outstanding matured in 2023. In 2024 the percentage of debt maturing is expected to rise to 33%. While the Federal Funds rate may have peaked for this cycle, the lagged effects on the rate of interest paid by the Treasury to borrow will be felt for a long time to come.

Another consequence of the rising cost to service the debt is that it can crowd out spending on Federal programs and services important to the public. For example, the CBO projects that in 2024 the Federal government will spend more on net interest cost on the public debt ($870 billion) than on national defense ($840 billion).

This crowding-out effect isn’t limited to the Federal budget. As the government debt burden grows other borrowers, like corporations and homeowners, may be forced to compete for funds. This could have the unintended consequence of driving up interest rates for borrowers generally.

The Challenge of Stabilizing the Debt

Most all agree the answer to the problem is to spend less and tax more while encouraging economic growth. But what to cut, who to tax, and how to promote growth are very challenging questions. Add growing partisanship and a continued willingness to ignore the issue and it is easy to see the problem.

Today’s environment is a case in point as Congress continues to disagree on how to fund fiscal 2024 spending, renewing the threat of a government shutdown. How will our leaders tackle the structural debt and deficit problems given routine tasks like funding the annual budget can’t be accomplished?

In the end, the solution will likely be one of shared sacrifice where all methods and means must be brought to bear to return the nation’s debt profile to a sustainable glide path. The burden cannot be absorbed by one generation or another. No single source of cuts or taxation can fix the issue. That may mean less spending across the board and the need to restructure entitlement programs, such as Social Security and Medicare. It may mean higher taxes. Any other outcome would increase the odds of further political division and generational conflict.

The Need for Urgency

While there are many ways to approach deficit reduction, ultimately, they need to get started. By procrastinating Congress makes these decisions more expensive and painful than they need to be.

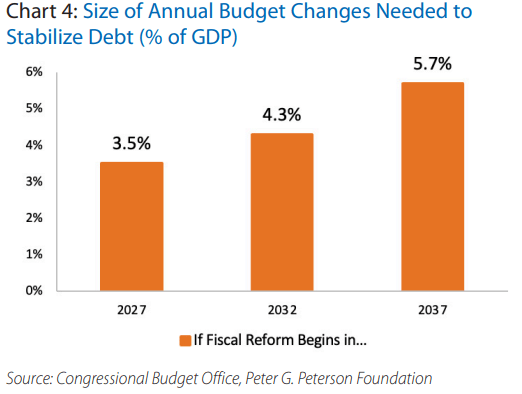

Using analysis from the Peter G. Peterson Foundation and CBO estimates, if fiscal reform were to begin in 2027 the cost, in terms of the size of annual budget change needed to stabilize the debt as a percent of GDP in the long term would be 3.5% (Chart 4). This means that the annual budget deficit would need to be reduced by 3.5% of GDP, and then held at that rate in ensuing years. A painfully big number but not impossible. If they wait until 2032 then the size of the budget change needed rises to 4.3%. The longer they wait the greater the size of the needed adjustment.

To better understand the scope of these adjustments, consider if Congress was to enact legislation in 2027 to raise taxes and cut discretionary outlays by a total of 3.5% of GDP. Based on current CBO assumptions it would require a deficit reduction of $1.1 trillion that year. Assuming half that amount was sourced via higher taxes and the other half from spending cuts, it would require a 10% lift to total tax revenue and a 30% cut to discretionary spending, leaving mandatory outlays, like Social Security and Medicare, untouched. These changes would still leave the overall budget at a deficit of -$529 billion. In future years revenues could grow with GDP, but outlays would need to grow less than GDP to achieve budget surpluses and debt reduction.

If Congress were to wait until 2032 to enact proportional changes to revenue and discretionary outlays totaling 4.3% of GDP, taxes would need to increase by 12% and discretionary spending would need to decline by 41%. Whether such cuts could be sustained and what that would mean for mandatory spending is an open question, but certainly, the sooner Congress acts the better.

Congress could take a more incremental approach, though it wouldn’t change the magnitude of the adjustment needed over time.

Could High Interest Rates Encourage Change?

While this sobering assessment can be discouraging, higher interest rates, the very thing exacerbating the problem today, can play a role in driving change.

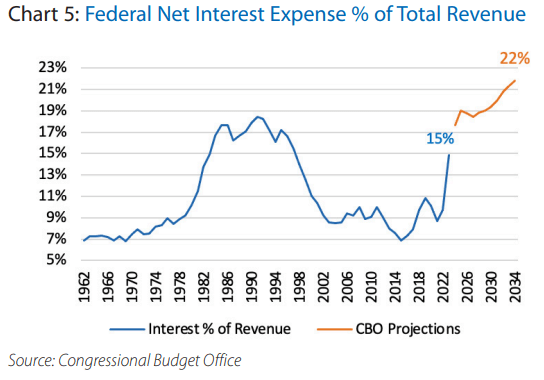

Federal net interest expense as a percentage of total tax revenues has been climbing quickly and at 15% is at its highest since the mid-1990s. This ratio is expected to continue to rise in the coming years, potentially crowding out discretionary spending and making it increasingly difficult for Congress. In fact, CBO projections suggest the ratio will rise to 22% by 2034 (Chart 5).

Yet history has shown that when this measure approached levels above 17%, it motivated government policy change. The last time we were at these levels was during the mid-1990’s, after a period of intense deficit spending related to defense in the waning days of the Cold War. In response a bipartisan group of congressional leaders negotiated with the President to create a package that reformed spending and revenue, allowing for several years of budget surpluses and debt stability at the Federal level.

Today calls for a bipartisan fiscal commission have grown and 9-out-of-10 voting Americans polled support its creation. In January the House Budget Committee passed the Fiscal Commission Act of 2023, with bipartisan support. The Chair of the committee has publicly stated that both revenue and expenditure changes must be on the table. These are the first steps toward creating a process that allows lawmakers to look across the entire budget for spending and revenue reforms.

Higher Interest Rates to Stay?

Progress on the policy front is needed for many of the reasons already cited. But also, because the current debt trajectory raises the likelihood that longer-term interest rates remain higher than they otherwise might. Treasury investors may demand a premium for continuing to fund runaway government deficits and, as the required increase in Treasury debt issuance forces competition for investor dollars across the capital markets. While the Fed’s tightening campaign to combat inflation certainly resulted in higher yields (Chart 6), investors must remain vigilant to the possibility that those yields could remain higher for longer with ongoing budget battles and fiscal issues.

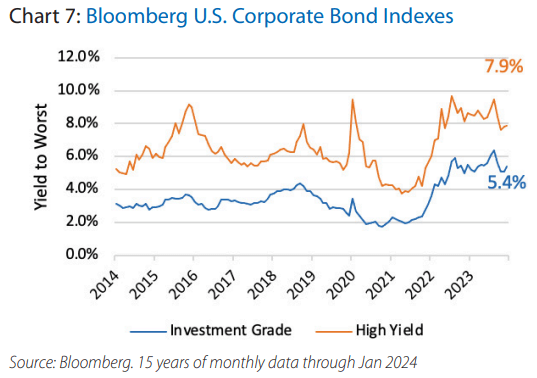

That said we expect that a soft landing for the economy and moderating inflation will be supportive of both equities and fixed income generally. We are attracted to current corporate bonds as their yields become more appealing as the rate of inflation falls (Chart 7).

We think that Congress will find a way to muddle through the current budget negotiations even if they are slow to make further progress on longer-term structural budget issues until after the election. Should a partisan breakthrough occur, we would expect markets to respond positively. Yet we remain vigilant to the possibility that volatility could continue as uncertainty around fiscal and monetary policy continues.

The Touchstone Asset Allocation Committee

The Touchstone Asset Allocation Committee (TAAC) consisting of Crit Thomas, CFA, CAIA – Global Market Strategist, Erik M. Aarts, CIMA - Vice President and Senior Fixed Income Strategist, and Brian Cheyne, CFA, CIMA - Senior Investment Strategy Specialist, develops in-depth asset allocation guidance using established and evolving methodologies, inputs and analysis and communicates its methods, findings and guidance to stakeholders. TAAC uses different approaches in its development of Strategic Allocation and Tactical Allocation that are designed to add value for financial professionals and their clients. TAAC meets regularly to assess market conditions and conducts deep dive analyses on specific asset classes which are delivered via the Asset Allocation Summary document. Please contact your Touchstone representative or call 800-638-8194 for more information.

The information provided reflects the research and opinion of Touchstone Investments as of the date indicated, and is subject to change without prior notice. Past performance is not indicative of future results. There is no assurance any of the trends mentioned will continue or forecasts will occur. Investing in certain sectors may involve additional risks and may not be appropriate for all investors. The indexes mentioned are unmanaged statistical composites of stock or bond market performance. Investing in an index is not possible.

Please consider the investment objectives, risks, charges and expenses of the fund carefully before investing. The prospectus and the summary prospectus contain this and other information about the Fund. To obtain a prospectus or a summary prospectus, contact your financial professional or download and/or request one on the resources section or call Touchstone at 800-638-8194. Please read the prospectus and/or summary prospectus carefully before investing.

Touchstone Funds are distributed by Touchstone Securities, Inc.*

*A registered broker-dealer and member FINRA/SIPC.

Touchstone is a member of Western & Southern Financial Group

Not FDIC Insured | No Bank Guarantee | May Lose Value