- The U.S. stock market has advanced by 10% since October even though the Federal Reserve has signaled monetary policy is on hold. This has caused some investors to question whether the Fed’s balance sheet expansion since then may be having an effect.

- Fed officials contend the action to step up purchases of short-term Treasuries is technical in nature and not a new round of quantitative easing (QE). Yet, many investors are not convinced and some view it as positive for equities.

- Our view is the balance-sheet actions may affect investor behavior even though this was not the intent. There is some resemblance to what occurred in 1999, when the Fed created excess reserves to protect against a possible Year 2000 (Y2k) disruption.

- However, we believe the principal driver of the stock market is the expectation the global economy will improve this year. While the coronavirus scare has increased uncertainty, its impact will likely be temporary.

Background

By all accounts the U.S. stock market experienced a powerful rally over the past year, with the S&P 500 Index having risen by about 30%. The consensus view among investors is a key driver was the reversal in U.S. monetary policy from tightening in 2018 to unexpected easing last year. Yet, the rally continued unabated in recent months, even though the Fed has indicated monetary policy is on hold indefinitely.

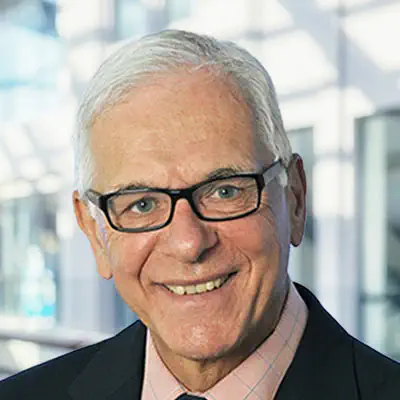

This situation has caused some observers to question whether Fed actions to expand its balance sheet is a factor.1 The circumstances are that Fed officials were surprised in September when the overnight repo rate surged to 10%, which is well above the rate they were targeting for fed funds. They concluded that the demand for excess reserves by banks (beyond what they are required to hold) was greater than expected. The Fed subsequently announced in early October that it would purchase Treasury bills at an initial pace of $60 billion per month to expand its balance sheet (Figure 1).

At the time of the announcement, Fed Chair Jerome Powell emphasized that unlike previous bond-buying programs called quantitative easing, or QE, the purpose of the operation was not monetary stimulus. Rather, the intent was to keep money market rates in line with the Fed’s goals. Fed officials have emphasized the operations are limited to shorter-dated government debt rather than longer-dated instruments, and that the balance sheet expansion will eventually be phased out. During the press conference that accompanied last week’s FOMC meeting, Powell indicated the purchases of short-dated Treasuries would continue into April, when most tax payments occur, but would be phased down thereafter.

Confusion About the Fed’s Actions

While Fed officials have reiterated the message that the balance sheet expansion is different from QE, there is still considerable confusion about what is happening. For starters, they have not explained why there is suddenly a shortage of bank reserves. Previously, the Fed was in the process of shrinking the balance sheet because officials believed economic conditions had normalized.

One explanation is that banks have become accustomed to holding excess reserves, because they receive interest payments from doing so. Excess reserves also serve as a cushion in the event there are unforeseen developments. And while the Fed could alter banks’ incentives by eliminating paying interest on excess reserves, it sees benefits in having an additional policy tool at its disposal.

Amid this confusion, the Fed is finding it difficult to convince investors that the balance sheet expansion is not an attempt to bolster the economy. In the end, if enough investors believe it will have a positive effect on the economy and markets, it could become a self-fulfilling prophecy. One risk in these circumstances is that investors could be disappointed if the U.S. economy and corporate profits do not improve in line with their expectations.

What Happened in 1999-2000

A vivid example is what occurred in the 1999-2000 time frame. At that time, the U.S. economy and stock market experienced a powerful expansion that rivals the current one in magnitude and duration. When the U.S. stock market plummeted in mid-late 1998 amid contagion from Asia, the Fed responded by lowering the federal funds rate three times, as it did last year.

Thereafter, the market went on to set record highs in 1999 as the Fed supplied excess reserves to the banking system. The reason: The Fed was worried that a glitch in computer systems not programmed to handle transactions beginning in the new millennium could trigger a run on the banks. Therefore, it opted to ensure the banking system would be sufficiently liquid.

Some investors mistakenly believed the Fed was easing monetary policy then, and they responded by purchasing stocks. The fallacy with their assessment was the reserves were simply held by banks as a precaution against possible Y2k disruptions, rather than being used to back new loans. The bull market subsequently ended in early 2000, when the Fed reversed course and tightened monetary policy.

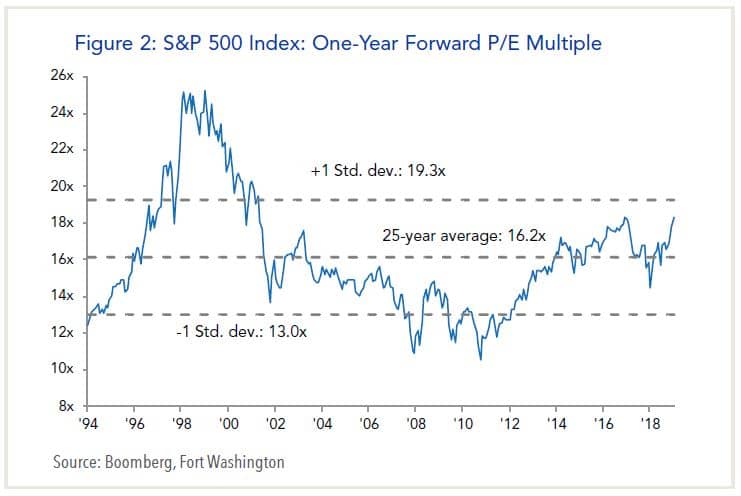

We do not foresee a repeat this time, mainly because stock market valuations are not as extended as they were 20 years ago (Figure 2). In this respect, the stock market is not in “bubble territory.” However, stock market valuations as measured by one year forward P/E multiples currently stand at 18 times, which is near the highs for the economic expansion.

The Coronavirus Scare

It is too early to determine how extensive the virus will be, how long it will last and what impact it will have on the Chinese economy. However, it is already proving to be more contagious that the outbreak of SARS in 2003, and forecasts for China’s growth in the current quarter are being scaled back below the government’s 6% threshold. Moreover, China’s impact on the rest of world is considerably greater today, as its share of the global economy has increased to 19% from 4.6% in 2003.

Our own assessment is the economic impact of the coronavirus will likely be temporary, as has been the case for most pandemics. Nonetheless, because it has occurred while the global recovery is nascent, a further sell-off in the U.S. stock market is possible if investors begin to doubt that the global economy will improve.