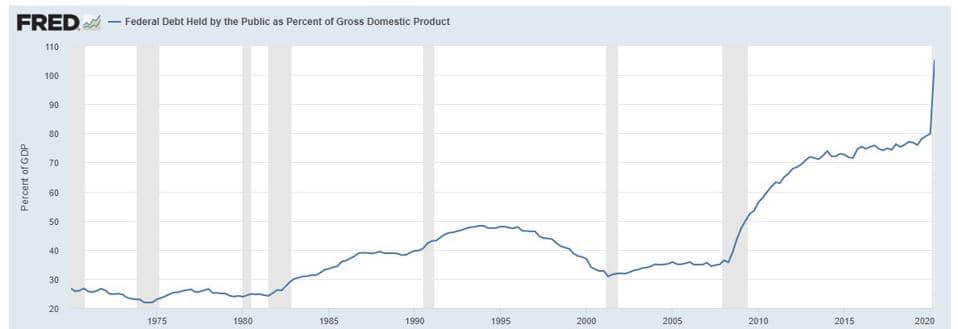

One issue that has perplexed fiscal conservatives for more than a decade is how Treasury bond yields have hovered at post-war lows despite a massive increase in federal debt outstanding. Since the onset of the financial crisis in 2008, publicly-held federal debt relative to GDP has increased from less than 40% to more than 100% this year, the highest in the post-war era. Yet, 10-year Treasury yields have breached 3% only briefly, and they are currently around 0.75%.

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. For informational purposes only. Shading indicates U.S. recessions.

By now, investors seem to be immune to outsized budget deficits in the wake of the coronavirus pandemic. The U.S. Treasury market, for example, did not react on Friday to news that the federal deficit for fiscal 2020 reached $3.1 trillion, or roughly 16% of GDP.

At the same time, U.S. voters do not appear unduly concerned even though many economists warn that current and prospective budget deficits are unsustainable over the long term.

What Accounts for This Ambivalence?

My take is that people do not worry about deficits as long as interest rates are low. Fiscal policy can impact bond yields either by altering inflation expectations or real (inflation-adjusted) yields. Over the past decade, both of these variables have been unusually low.

Fiscal conservatives see a link between large budget deficits and inflation. However, the U.S. experience suggests monetary policy rather than fiscal policy is the main driver of inflation. This lesson was learned during the 1980s, when the U.S. ran large budget deficits but inflation declined because monetary policy was highly restrictive. Nominal yields on U.S. Treasuries, in turn, declined as inflation and inflation expectations receded.

One fixture over the past decade is that inflation expectations have remained well anchored near the Federal Reserve’s inflation target of 2% per annum. This has occurred even though the Fed’s balance sheet has grown to more than $7 trillion from less than $1 trillion before the 2008 financial crisis.

When the Fed embarked on quantitative easing during the financial crisis some commentators warned that it would spawn higher inflation. But it never materialized. The principal reason is most of the increase in liquidity was held by banks in the form of excess reserves and did not influence aggregate demand.

The main challenge for the Fed since then has been to attain its annual inflation target of 2%. The Fed recently announced it would henceforth target an average annual rate of 2%. This means it is now willing to allow inflation to climb above that level if it was below 2% previously.

As the Fed implements its new strategy it confronts two types of challenges. First, can it achieve its stated goal? Second, if the 2% rate is exceeded can it convince investors it will not tolerate a permanent overshoot?

Of these, the first may be the most difficult considering how much time has passed since the Fed achieved its stated inflation objective. By now, policymakers and economists alike are wondering how well they understand the determinants of inflation: Neither the monetarist framework nor the Phillips curve model has done a good job of predicting inflation over the past two decades.

Several reasons have been put forth including the roles that globalization and rapid technological change have played in contributing to disinflation. Beyond this, inflation expectations have stayed low because of inertia. Thus, the longer inflation is low, the more convinced investors are that it will remain low.

Even if inflation stays tame, however, enlarged budget deficits could still impact the bond market by boosting real yields. This was evident, for example, in the 1980s when large budget deficits boosted real yields as high as 5%-6%, well above the historic average of 2%-3%. This occurred against a backdrop of strong economic growth in which increased government borrowing “crowded out” borrowing from the private sector.

This phenomenon, however, has not been evident over the past decade for two reasons. First, economic growth in the U.S. and abroad has been well below long-term trends. Second, business investment demand (and corporate borrowing) has been unusually soft. It has not responded to cuts in interest rates to record low levels or to cuts in corporate tax rates that were enacted at the end of 2017.

In the wake of the coronavirus-induced recession, yields on 10-year Treasury inflation-indexed bonds have fallen to an all-time low of minus 1%. Thus, with inflation expectations running in the vicinity of 1.7%, the nominal yield on the 10-year Treasury is only 0.7%. The bottom line is that investors should be prepared for Treasury yields to stay unusually low a while longer.

However, this does not mean what is happening is sustainable. According to the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), the current trajectory of U.S. federal debt implies that publicly-held federal debt would double to 195 percent of GDP by 2050. CBO concludes that the prospective debt path would “raise borrowing costs, reduce business investment, and slow the growth of economic output over time.” In this respect, the costs of outsized deficits may not be apparent now, but they will become more visible in the future if federal spending is not brought under control.

A version of this article was originally posted to Forbes.com on October 20, 2020.