Overview

Since the financial crisis of 2007-2008, the word "subprime" has carried a negative association for many investors, due to the role that subprime mortgages played in the housing crash. While this aversion is a natural response to such a crisis, it is often painted with too wide a brush, particularly concerning the auto finance industry. Approximately one-third of all U.S. consumers carry a credit score of 670 or below, placing them in the subprime category. While these borrowers have a higher likelihood of defaulting on a loan compared to their prime peers, lenders have various ways to properly account for that risk when financing a vehicle purchase. These may include charging a higher interest rate, offering a lower advance rate (lending a lower dollar amount relative to the value of the vehicle), or requiring a higher down payment from the borrower. When underwriting and loan structuring are done properly, subprime auto financing can fill a critical gap in the consumer finance market—helping to satisfy a transportation need (and likely an employment need) for a large segment of the consumer base that may not otherwise be able to obtain traditional bank financing.

The subprime auto financing and securitization industry has been tested and refined through multiple economic cycles. Investors today have a wealth of historical data useful for analyzing the universe of subprime auto asset-backed securities (ABS). The market offers a wide range of risk/return profiles ranging from very short duration/high quality, to intermediate duration/speculative-grade quality, providing potential utility for a wide range of investment needs. Investors equipped with the necessary tools and resources to properly evaluate this sector have the opportunity to benefit from the diversification, relative value, and investor-friendly structural attributes that it offers.

While many investors dismiss this large segment of the consumer base as "too risky," our objective is to highlight some of the historical and structural attributes of subprime auto ABS that merit a closer look.

Table of Contents

Background: Subprime Automobile Financing

To understand the modern-day subprime auto securitization market, it can be helpful to first review the history and evolution of automobile financing over the past century. When Henry Ford introduced the Model-T in 1908, he had a vision of mass-producing affordable vehicles suitable for widespread ownership. To realize this lofty goal, he needed a cost-effective way to produce the vehicles—eventually yielding his invention of the assembly line in 1913. The assembly line solved the problem of mass production, but it also created a new problem: how to clear the vehicles out of the factories as quickly as they were being produced. Car dealers were purchasing inventory from Ford to sell to consumers, but they were not able to purchase vehicles in bulk quickly enough to keep factory production flowing. In 1919, Ford's top competitor, General Motors, took the innovative step of forming General Motors Acceptance Corporation (GMAC), to address that concern. GMAC's purpose was to provide financing for dealers to purchase large inventories of vehicles, and also to help customers secure financing conveniently at the dealership. This bridged a critical gap in the consumption pipeline, helping consumers obtain an expensive durable good during a period when the Federal Reserve was explicitly warning banks not to finance automobiles that are "used for pleasure" rather than for income-generating purposes such as farming. Skeptical of the usefulness and durability of the automobile, Federal Reserve governor Maximilian B. Wellborn stated "…I do not believe…the credit structure should be called upon to bear the burden of financing automobiles that are used for pleasure purposes."

While GM forged ahead with its creative funding solution, Henry Ford took a more conservative approach aligned with Wellborn's view. Instead of offering customers credit, Ford offered them a lay-away plan: make payments until you have paid the full price, then take delivery of the car. Customers made it clear that instant gratification was the preferred route, and in 1928 Ford followed in GM’s footsteps by establishing its own auto lending subsidiary. By 1930, more than two-thirds of vehicle purchases were being financed (more than 85% are financed today).

By the mid-20th century, banks and credit unions had joined the auto financing landscape for high-credit quality borrowers, while some Thrift Banks and Savings & Loans were extending credit into the subprime space. In 1972, Michigan businessman Don Foss founded Credit Acceptance Corporation in the Detroit suburb of Southfield, pioneering the first independent lending effort specifically focused on subprime borrowers. Foss’s success paved the way for a burgeoning industry of peers, including Ugly Duckling Finance Corp (now DriveTime), Consumer Portfolio Services, and many others.

Securitization

Forty years prior, the U.S. economy was in the throes of the Great Depression. With one-fourth of the total workforce unemployed, the escalation of mortgage delinquencies was placing enormous stress on banks' balance sheets, preventing them from continuing to lend. To address this, Congress passed the National Housing Act of 1934, which provided incentives for banks and lending institutions to continue to provide financing to consumers. In 1938, Congress chartered The Federal National Mortgage Association ("Fannie Mae") with a $1 billion budget to purchase mortgages from lenders, freeing up capital and further resuscitating the lending pipeline. Eventually, in 1968, Congress established The Government National Mortgage Association ("Ginnie Mae") program as an off-shoot of Fannie Mae, to further expand access to home ownership for Americans by providing a full guarantee to lenders (backed by the full faith and credit of the U.S. government) for qualified mortgages they originated. Even with this additional benefit, however, lending activity was still being constrained by banks' limited capacity for retaining those guaranteed mortgages on their balance sheets. To alleviate that bottleneck, Ginnie Mae developed the first modern-day Mortgage-Backed Security (MBS) in 1970. By pooling mortgages together and converting them into a marketable security, Ginnie Mae provided an outlet for bank lenders to clear mortgages off their balance sheets, thereby connecting everyday American homebuyers to the institutional capital markets.

Financial markets recognized that this model of securitization would be applicable to other types of financial assets. By 1985, the concept had spread into the non-mortgage space, as Sperry Lease Corporation packaged a portfolio of computer lease receivables into a securitization, selling $200 million of AAA rated notes to investors. Soon after, Valley National Bank and Marine Midland pioneered the inaugural securitization backed by auto loans, catching the attention of the entire auto industry. A number of other auto lenders would package their loans into securities as well, including Western Financial Savings & Loan ("Western Financial"). Western Financial had accumulated a portfolio of subprime auto loans during its days as a Thrift & Loan. After converting to a Savings & Loan in order to access depository capital, regulatory requirements necessitated a reduction in subprime auto loan exposure relative to the company’s mortgage portfolio. Western Financial engaged high yield banking firm Drexel Burnham Lambert, which underwrote the industry’s inaugural Subprime Auto loan backed securitization, successfully off-loading Western Financial's portfolio in December 1985—just before the firm’s regulatory deadline at year end. These early deals increasingly garnered the attention of the auto finance industry at large, including the manufacturers’ captive auto lenders.

The Early Days: A Bumpy Ride

As securitization proved a viable source of financing for auto loans—both prime and subprime—the marketplace of originators expanded rapidly. Many new, thinly-capitalized specialty finance companies were established, with aggressive growth aspirations and weak credit models. Underwriting processes were rudimentary, neglecting to incorporate historical data into the credit decision-making process. Many new originators were focused on quickly scaling up loan volume and accessing institutional capital markets—both by securitizing their loan portfolio and by raising equity in the public markets. Securitizations were structured with limited “hard credit support” by modern-day standards (built-in structural protection from subordination and excess collateral). Instead, they typically relied on a third party insurance policy (“wrap”) to obtain an AAA rating on the senior tranches.

As subprime auto origination volume ballooned into the early/mid 1990s, defaults began to escalate beyond expectations as a result of poor underwriting practices and a hypercompetitive lending environment. As losses mounted, many newer lenders of the day were eventually forced into bankruptcy, while several firms including Mercury Financial, First Merchants, and National Auto Credit, faced allegations of fraud as management teams frantically attempted to hide losses from investors. Equity holders and bank warehouse providers bore the brunt of the unexpected losses, while insurance wraps largely made securitization bondholders whole. However, some small subordinate tranches which lacked insurance coverage were exposed to principal losses.

As a result of the subprime auto bust of the 1990s, market participants learned to place greater emphasis on lender/issuer due diligence, and lenders learned the importance of developing more robust credit and risk models supported by historical data. Subprime auto lenders who were active in the early 2000s were better-capitalized and had more sophisticated underwriting capabilities compared with their weaker counterparts from the decade prior. Credit support requirements for securitizations were also increased relative to levels of the prior decade, although many structures in the early 2000s still used insurance wraps to obtain the desired credit ratings.

The Global Financial Crisis

As the Global Financial Crisis brought markets to a halt in 2007/2008, lenders—including subprime auto lenders—lost a critical source of capital in the securitization markets. Markets would remain effectively closed for nearly two years, with the exception of some deals facilitated by the Fed’s Term Asset-Backed Securities Loan Facility (TALF).1 Subprime auto lenders were forced to drastically cut loan volume, and in some cases halt lending altogether. The implications for the consumer were immediate, as it became nearly impossible for would-be borrowers to obtain credit for purchases for homes, vehicles, and other commonly financed assets. The prospects for existing securitizations were not immediately clear. The unemployment rate more than doubled to 10%, and delinquency rates on outstanding auto loans began to climb. Subprime auto lenders reduced their origination staff or repurposed them as loan servicing personnel to help bolster collection rates, as the industry braced for its second major test in as many decades.

While the subprime auto ABS market of the 2000s consisted of issuers with stronger balance sheets and stronger credit underwriting capabilities compared to their 1990s counterparts, most securitizations were only structured to satisfy a low-investment grade rating based on hard credit support alone. Deals still largely relied on an insurance wrap to achieve an AAA rating for senior tranches. In spite of the subprime auto-related claims that insurers paid during the 1990s, bond insurance was still a cost-effective way for issuers to achieve the desired credit ratings for their bonds, as competition among bond insurers kept rates attractive. While insurance providers were readily able to absorb the subprime auto losses of the 1990s, the housing-related obligations stemming from the Global Financial Crisis would ultimately be more than they could withstand. As bond insurance claims mounted for housing-related securitizations, rating agencies downgraded the insurance wrap providers—and the subprime auto ABS securities whose ratings depended on them.

The strong performance of subprime auto ABS through the Global Financial Crisis is widely accepted as having validated the modern-day securitization model for the sector.

Notwithstanding the stresses on the market, there were several forces at play which helped support subprime auto securitization performance through this period.

- First, auto issuers maintained significant alignment of interests with securitization bondholders by retaining meaningful first-loss exposure on their own balance sheets. This exposure, known as "residual interest," was subordinate to the ABS notes outstanding, providing a direct economic incentive for issuers to optimize portfolio performance for both themselves and for securitization noteholders.

- Secondly, delinquency data across consumer credit sectors would eventually show that borrowers prioritized auto loan debt obligations over all other types of consumer credit during this time period—choosing to pay their car loan over even their mortgage when forced to choose one over the other. This phenomenon of consumer payment prioritization hierarchy, combined with the originators’ robust credit underwriting models, resulted in delinquency and loss rates which were lower than originally feared, and generally within the range of stress levels that the securitization structures were able to withstand without the support of the defunct insurance wraps.

Auto ABS ratings have been consistently dominated by upward migration.

While there were some rare instances of speculative-grade (rated BB+ and below) subprime auto ABS which took losses through the Global Financial Crisis, bonds rated investment grade (BBB- or better) were able to weather the downturn. This remarkable performance through the most severe economic recession since The Depression is widely regarded as having validated the modern-day subprime auto ABS model.

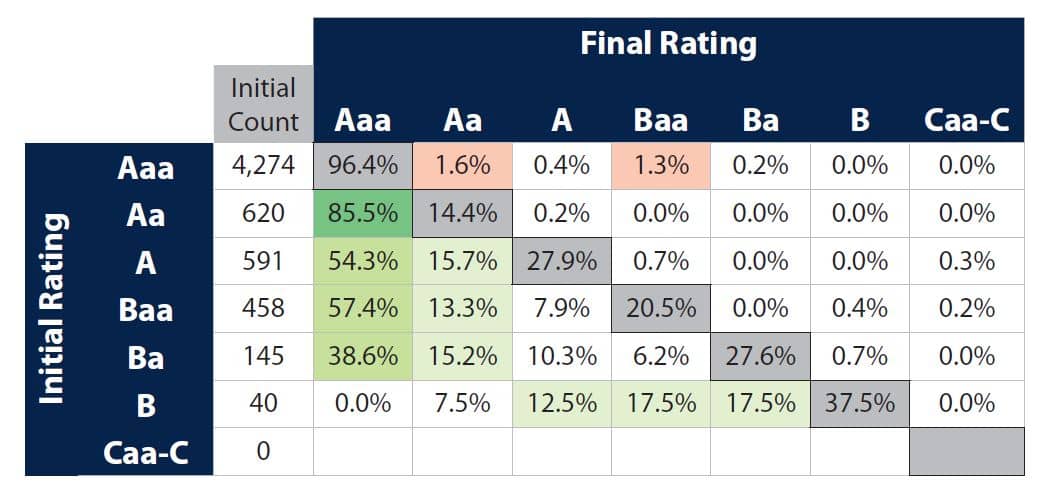

The table below shows cumulative, life-to-date ratings migration for U.S. auto loan ABS from 1993 to 2021, using the final rating before withdrawal for securities that have paid off or matured. Notably, even through the stresses of the 1990s and the insurance wrap-driven downgrades of the Global Financial Crisis, the degree of downgrade and impairment activity is quite minimal, particularly for the investment grade rating categories. As shown below, the upward ratings migration trend is dominant:

Source: Moody's Investor Service.

Modern Day: Continuing on the Road to Growth

Bond Structures

Since the Global Financial Crisis, markets have continued to refine and develop the subprime auto ABS model. Securitizations generally no longer use insurance wraps, but instead are structured with even higher hard credit support levels than they were prior to the Global Financial Crisis. For investment grade rating categories, bond classes are structured to withstand multiples of the base case level of expected losses. In order to achieve an AAA rating, for example, a subprime auto ABS bond may be required to withstand anywhere from 2.5x to 4x the actual expected level of losses (the “loss coverage multiple”). This might correspond to initial hard credit support level of 50-60%, for example, which would be sufficient to protect the bond from default rates significantly higher than what was experienced during the Global Financial Crisis. The loss coverage multiple requirements for each rating category vary by rating agency, and are also influenced by numerous deal-specific and collateral-specific factors.

In addition to hard credit support, subprime auto ABS also benefit from a form of credit support called excess spread. While overcollateralization compares the outstanding principal balance of the underlying automobile loans to the principal balance of the ABS notes outstanding, excess spread quantifies the difference in interest rates between the two. A pool of subprime auto loans, for example, is likely to accrue interest at an average rate of 12-25%. The ABS notes those loans support, however, may only have an average coupon of 2-4%. Even when adjusted for expected delinquencies and defaults, this excess spread provides significant additional cashflow to the securitization trust, which can help pay down the notes more quickly than the underlying collateral is paid down. This results in a phenomenon known as “deleveraging,” whereby the risk profile of the ABS notes improves as the loan pool ages, resulting in a consistent trend of rating agency upgrades in the subprime auto ABS sector over time.

While it is important to understand nuances between securitizations, subprime auto ABS structures have generally been consistent in the post-crisis era. The sector is widely recognized as having been time-tested and proven through multiple periods of stress including: the Global Financial Crisis, a moderate industry overheating/correction in 2015-2016, and most recently the brief but extreme impact of the COVID-19 lockdown and subsequent recession. While the sector has passed these stress tests with flying colors, it is crucial for investors to maintain a critical eye as they evaluate structural nuances and make their own assessment of each deal.

Issuer Expansion

In the post-financial crisis era, many new subprime auto lenders have entered the market, while many seasoned lenders have begun securitizing their assets for the first time. It is critical that investors take the time to properly underwrite each program individually, from a number of perspectives:

- Operating History: Issuers with a long, stable track record of consistent lending are likely to have greater predictability of collateral performance going forward. Alternatively, issuers with a shorter operating history, or with significant changes in lending practices or collateral attributes over time are likely to have greater variability in collateral performance. Investors should evaluate an issuer’s historical track record to determine not only performance expectations going forward, but also a degree of certainty around those expectations.

- Alignment of Interests/Ownership Structure: On the heels of the financial crisis, Basel III regulation established minimum risk retention requirements to ensure a baseline level of alignment of interests between securitization issuers and investors. For the vast majority of subprime auto issuers, these new requirements were a very low hurdle, given that they already were retaining significantly more residual exposure than what Basel III mandated. While some subprime auto lenders in the 1990s fell victim to their private equity owners’ aggressive growth targets, today’s sector is dominated by strong alignment of economic interests between ABS investors and company ownership. This can help mitigate investors’ concern around the private equity ownership that is still fairly common in the subprime auto sector today.

- Management Teams: Many subprime auto ABS issuers in today’s market have strong, stable management teams in place, with decades of relevant experience operating through a variety of different market environments. Even so, it remains valuable for investors to evaluate each management team for any red flags or areas of potential concern, to assess continuity within the company, and to identify any areas of risk in how management executes the company’s strategy. This may include assessing the company’s ability to scale up operationally, to effectively manage any geographic expansion, or to facilitate any other type of complex strategic plan.

- Credit Underwriting Capabilities: Many subprime auto issuers can coherently account for historical trends in collateral performance by pointing to specific strengths or weaknesses in a particular generation of their underwriting model, or by addressing specific competitive forces at play at certain points in time. Some issuers are able to demonstrate predictive power of their underwriting model and risk-scoring capabilities, while others have a more reactive approach—adjusting credit or pricing models in response to unexplained deviations in collateral performance without understanding what variables drove those performance deviations. While issuers’ credit process presentations may seem similar at the surface, investors should take the time to understand each model in greater detail in order to better differentiate between programs.

This list of issuer underwriting topics is far from comprehensive, but it is intended to illustrate the types of ways in which subprime auto ABS investors can assess and distinguish between the varying risk profiles of issuers. Ideally, markets should efficiently rank issuers by linking the best execution (lowest cost of funds) to the strongest issuers, and by demanding a premium (higher cost of funds) for weaker ones. In reality, the steepness of the compensation curve fluctuates between generous and negligible over time, and investors must choose whether risk premiums are adequate for the various risk profiles offered in the market. The marketing process for subprime auto securitizations typically affords investors the opportunity to thoroughly underwrite each program—a critical component of the investing process in our view. We choose to take advantage of this opportunity to fully diligence each lender’s business model and develop a dialogue with each issuer with whom we choose to invest.

Market Development & Opportunity

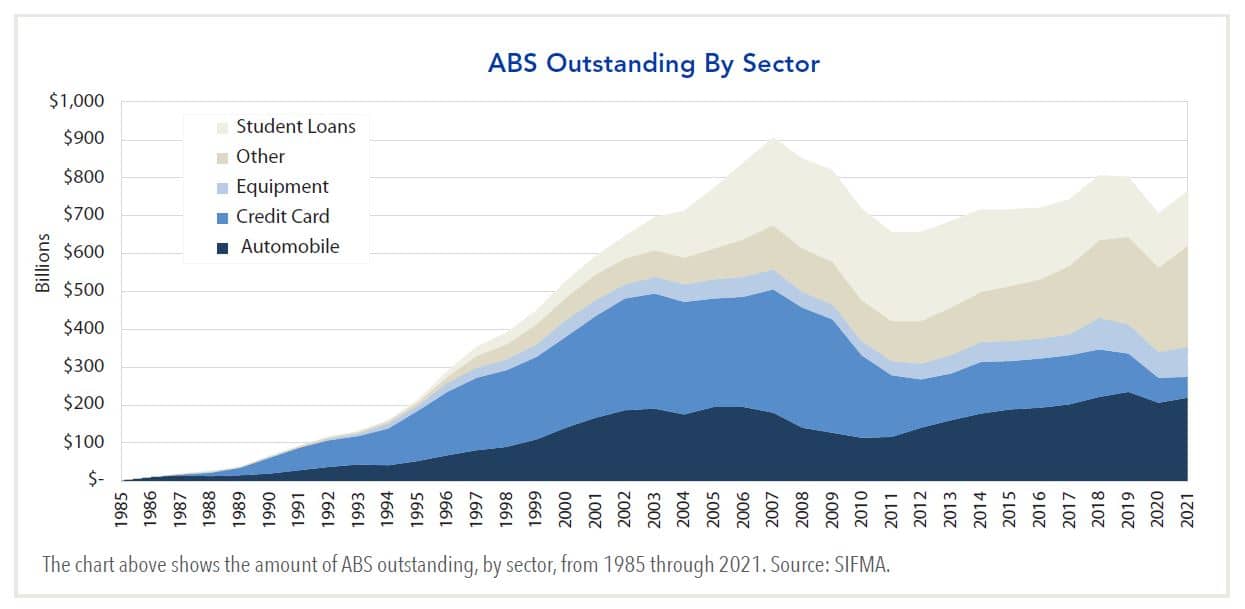

As the subprime auto securitization market has continued to expand and evolve over the years, market participation and depth has also grown. Subprime auto ABS now represents more than $40 billion outstanding of the broader $220+ billion auto ABS market. With numerous investment banks providing warehouse financing as well as banking and syndication services to these subprime auto lenders, secondary markets are active and well established. Furthermore, FINRA’s Trade Reporting and Compliance Engine (TRACE) now requires full trading transparency for secondary activity in the ABS market.

For investors who are equipped to do the necessary analysis and surveillance, subprime auto ABS offers a wide spectrum of risk/return profiles from which to choose. Risk profiles available vary widely by interest rate risk (duration), credit risk (AAA down to B or even unrated), and cashflow profile (from immediately amortizing profiles to more bullet-like cashflows), which may vary based on an investor’s modeling assumptions (delinquency and default rates, prepayment speeds, recovery rates). Furthermore, for bonds trading at a premium or discount dollar price, these modeling assumptions can have a meaningful impact on the yield earned, thus creating a risk/reward opportunity on which properly-equipped investors can capitalize. Investors can benefit from all this, as well as many of the broadly relevant structural tailwinds (e.g. excess spread) that are most acutely beneficial to the subprime auto segment of Auto ABS.

While the 1990s provided a necessary correction to address some of the early weaknesses of the subprime auto model, the sector has since developed into one of the most fundamentally durable and consistent segments of the bond market. As shown above, growth in subprime auto securitization over the past 20+ years has been modest and well-managed. Securitization provides one outlet for auto lenders who choose to sell the loans they originate; however, it has generally represented only 15-30% of total auto lending over time. This reflects the meaningful proportion of loan origination volume that lenders maintain on their own balance sheets—banks, credit unions, and other finance companies. This creates the strong alignment of interests that has helped support the continued healthy development of the sector over the past 20 years.

Summary

Nearly four decades old, the subprime auto ABS sector has matured into a robust, core component of the consumer finance ecosystem and the securitized products market. With a healthy mix of strong legacy operators and younger new entrants, investors have a wide range of issuer types and risk profiles from which to choose. The subprime auto ABS securitization structure has been tested and refined through multiple stress cycles, providing markets with a wealth of historical performance data from which to draw conclusions about performance expectations going forward. While issuer-level and bond-level due diligence remains critical, investors have seen that the standard structural attributes of subprime auto ABS present a solid protective backdrop via strong credit enhancement levels, meaningful excess spread, and a tailwind of structural deleveraging as deals age. While this segment of the market requires a distinct set of tools and resources for proper evaluation, it also has the potential to provide a unique risk/return profile which may be beneficial for investors who are properly equipped to evaluate the space.