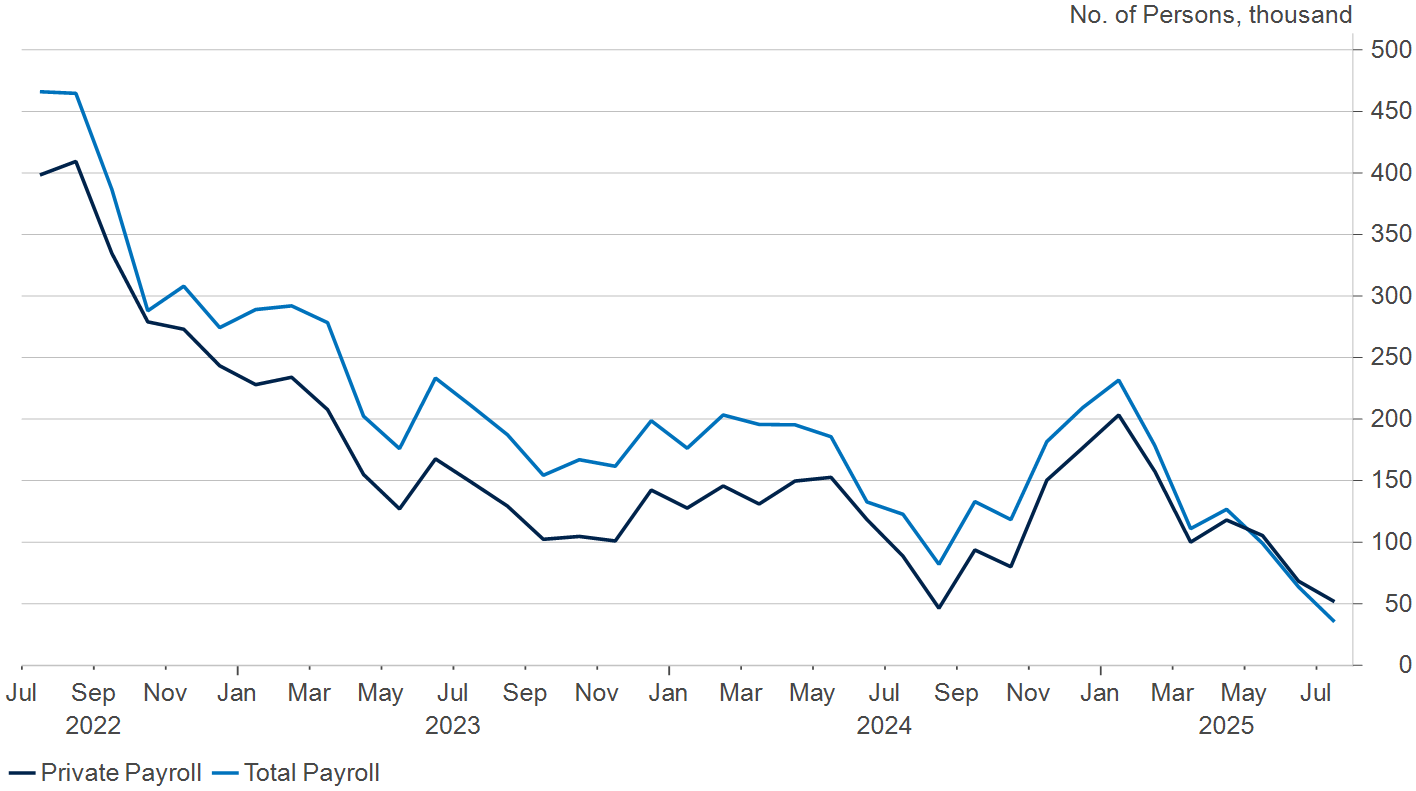

The July employment report came in weaker than expected, but the bigger story is that jobs creation in the prior two months was revised down by 258,000. This has altered perceptions of Federal Reserve (Fed) officials and investors about the strength of the labor market, and it could presage Fed easing in September if the August jobs report confirms the labor market is soft. Treasury yields declined on the news, while the stock market and the dollar sold off.

The three-month moving average for nonfarm payrolls has now fallen to just 35,000 in the last three months, the lowest since the pandemic, from more than 200,000 at the start of this year (see Figure 1). The July payroll gain was narrowly based, and the run rate for private payrolls, excluding health and education, was flat over the past three months.

Manufacturing jobs fell for a third consecutive month to the lowest level in more than three years. July’s purchasing manufacturing index also disappointed expectations, falling by one percent to 48%, with its outlook clouded by tariff uncertainty.

Figure 1. Nonfarm Payrolls, 3-Month Moving Average Change in Thousands

Nonfarm Payroll (3M MA)

The pace of job growth was not sufficient to keep the unemployment rate steady. It rose to 4.25% from 4.10%, even though the labor force participation rate dropped by a tenth to 62.20%.

Rising Unemployment Amid Cooling Momentum

The July jobs report also came on the heels of data that showed economic momentum is cooling. Although real GDP rebounded at a 3% rate in the second quarter owing to a steep decline in imports after the April 2 “Liberation Day” announcement, final domestic demand rose at only a 1.2% rate.

At the same time, progress in lowering inflation has stalled, with the core CPI rate in June just below 3%. The Fed took this into account when it kept interest rates unchanged at the July FOMC meeting.

However, Fed Governors Christopher Waller and Michelle Bowman dissented on grounds that the job market was softening, and price increases associated with tariffs represented a one-time increase rather than an ongoing source of inflation. This will likely frame the debate at the next FOMC meeting in September.

Tariff Uncertainty Complicates Policy Decisions

The current consensus of the Fed is that uncertainty about how tariffs have been rolled out makes it difficult to decipher how they are impacting the economy and inflation. Therefore, the Fed should wait to alter monetary policy until it has a clearer read on the economy.

Trade deals announced prior to the August 1 deadline for negotiations have provided some clarity in what President Trump is seeking. The baseline for most countries is in the area of 15%-20%, with some receiving higher duties on grounds they did not negotiate in "good faith." The latest estimate of the Yale Budget Lab Model is that the effective tariff rate for the U.S. is 18%, the highest since the 1930s, versus just over 2% at the start of this year.

There is considerable uncertainty nonetheless about details of the agreements. Some observers liken them to handshakes rather than formal agreements that will be ratified by the respective governments. The legality of the deals is also being challenged in U.S. courts on grounds that the International Emergency Economic Powers Act does not grant the president authority to impose across-the-board tariffs.

In a CNBC interview, Atlanta Fed President Rafael Bostic pushed back on the idea that the impact of tariffs on prices is one-time. He observed that higher tariffs are now a permanent fixture of the U.S. economy, rather than a negotiating tool as many believed. This implies that businesses will have to alter supply chains, which could add to their costs.

In a note to clients, Jim Glassman wrote that tariffs would show up very gradually in monthly price readings. He concludes: "Customs duties, which are headed to consumers, probably will top out at $325 billion annually and that will add about a percentage point to all the other factors affecting this year’s CPI."

Weighing these considerations, my take is that the Fed could resume policy easing in September if the August jobs report confirms the labor market is soft.

Future rate cuts, however, are likely to be gradual considering inflation is drifting away from the Fed’s 2% target and the economy does not appear on the cusp of recession. In the meantime, investors will probably shrug off demands by President Trump for the Fed to lower interest rates to 1%.

What Does All of This Imply for the U.S. Stock Market?

My assessment is that the powerful market rally since mid-April reflected two key considerations. The first was that President Trump would reconsider following through on his tariff threats. The second was that the fallout from higher tariffs would not be as bad as many economists were calling for.

In light of recent developments, however, it is now clear that Trump was able to implement the highest increase in tariffs since the 1930s, and he intends to keep them in place indefinitely. Meanwhile, the impact of heightened uncertainty on the U.S. economy is increasingly apparent, and the expected price hikes from tariffs are just beginning to unfold. If so, the U.S. stock market may confront greater headwinds ahead.