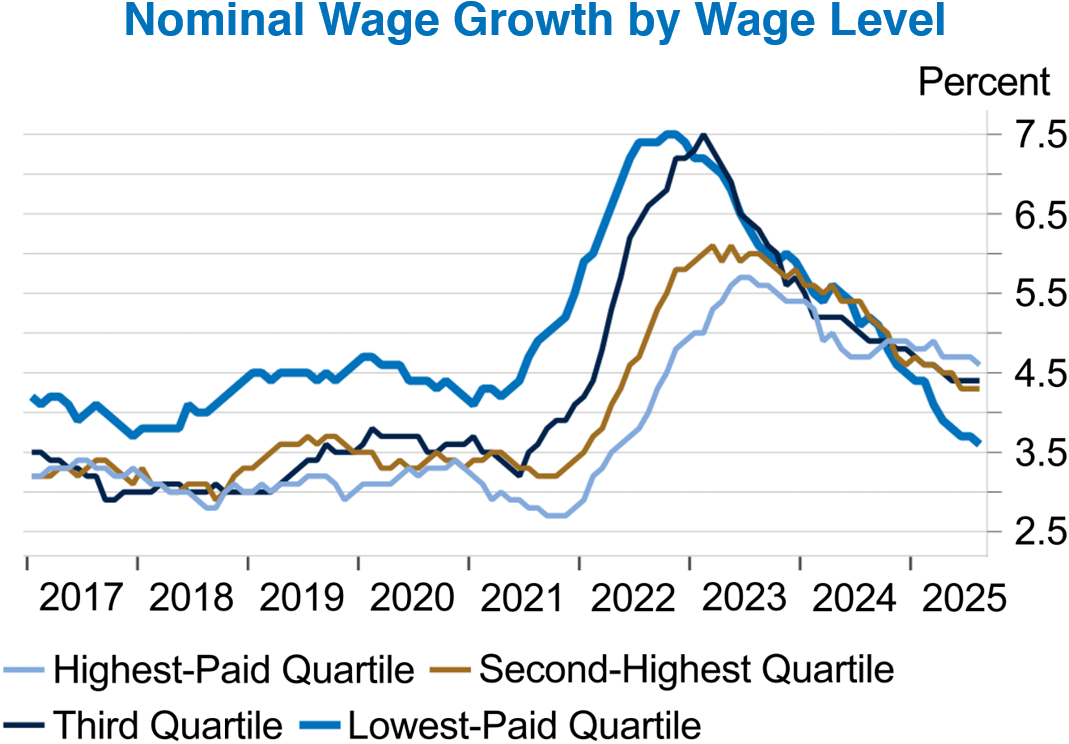

The state of the U.S. consumer has become a tale of two very different stories. On one side, the high-income consumer appears fundamentally solid. Rising stock and home prices, combined with steady income growth, have fueled a strong “wealth effect,” and these consumers have been the primary drivers of economic growth over the past few years. Conversely, lower-income households are under pressure as excess savings have largely dried up and wage growth has fallen behind that of higher earners. This divergence—often described as a “K-shaped” economy—has drawn attention from both Wall Street and Main Street, given that personal consumption accounts for nearly 70% of GDP.

Despite solid aggregate consumption data, consumer sentiment remains historically weak. Much of that pessimism stems from the large share of Americans who fall into the more financially strained category. Only about the top 10% of income earners own equities, meaning most households haven’t benefited from rising asset prices. Many of these consumers don’t own a home and instead have faced higher housing costs through rising rents, alongside elevated prices for groceries, cars, and other essentials. Access to credit has also dried up for these borrowers, widening the spending gap between the two consumer groups.

This bifurcation is also evident within consumer-oriented securitization markets. Subprime auto asset-backed securities (ABS)—pools of auto loans to lower-credit-quality borrowers (FICO below 620)—have seen delinquencies and losses rise meaningfully over the past few years. Interestingly, while delinquency rates now exceed those seen during the Global Financial Crisis, loss rates remain roughly in line with 2019 levels. This suggests borrowers are doing everything possible to avoid losing their vehicles even after missing payments—a sign of limited savings and very little margin for unexpected costs.

Also within the subprime auto space, issuer performance has diverged. Some issuers have proven adept at underwriting in this environment, effectively pricing and modeling expected losses—albeit at higher nominal levels. Other issuers, however, have struggled to manage loss rates within expectations despite progressively tightening credit standards over the past two to three years. This K-shaped trajectory in the market’s perception of issuers has driven wider spread tiering across the sector.

Bifurcation itself is not new, but it continues to permeate both the macroeconomic landscape and the investment environment. While we expect consumer spending to pick up in 2026 and support economic growth, this underlying divergence reinforces the importance of careful credit selection. For investors, it underscores why active management remains critical—particularly within securitized products, where dispersion among issuers and borrowers can be pronounced.

Chart sources: Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta and Macrobond.Download Impact of the K-Shaped Economy on Fixed Income Investors

Download Impact of the K-Shaped Economy on Fixed Income Investors